Neuropathogenesis

RVFV infection of humans results in at least 3 distinct clinical outcomes: acute Dengue-like febrile illness, severe hepatic/hemorrhagic disease, or encephalitis. Either of the two severe forms of RVF (hemorrhagic or neurologic disease) occur in 1-5% of naturally infected patients; however, the incidence of neurological disease may be increasing. Whether exposure route determines clinical outcome is not fully known, but people exposed to RVFV when handling infected animal carcasses have a 4X greater incidence of one of the more severe forms of disease. In line with this, our data suggest that RVFV is more lethal and more likely to cause neurological disease when administered by aerosol rather than subcutaneous infection.

Development of effective antiviral therapeutics for treatment of neurological disease caused by RVFV requires a detailed understanding of the neuropathogenic mechanisms. Our projects strive to identify key pathogenic mechanisms in the development of RVF encephalitis which will then guide the evaluation of effective antiviral therapeutic treatment regimens applicable to neurological RVF. See Walters et al. 2019 and Albe et al. 2019.

We just published a new review article on the neuropathogenesis of RVF!

In utero transmission

RVFV is a veterinary disease, and vertical transmission and fetal death are hallmarks of disease in sheep and cattle infected with RVFV. Data from human outbreaks, while limited, suggest that vertical transmission of RVFV to the developing human fetus can occur with detrimental outcomes.

Given the high incidence of fetal infection in livestock and the potential for such transmission in women, we sought to develop a tractable rodent model in which to experimentally study RVFV infection during pregnancy. Initial studies demonstrated that infection of immunocompetent, late-gestation Sprague-Dawley rats with a wild-type pathogenic strain of RVFV resulted in transplacental transmission and infection of fetuses with adverse outcomes, including intrauterine death. These results provide a foundation for studying the mechanisms of vertical transmission of RVFV and a model for evaluating vaccines and therapeutics for efficacy in protecting developing fetuses. See McMillen et al., Science Advances 2018.

See also our recent review article that came out in JVI.

Just published is our detailed pathological study of the effect of RVFV infection in the placenta!

Host entry factors

How arboviruses like Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) are able to infect a huge range of species from mosquitoes to animals remains largely unknown. We recently identified the ubiquitous and highly conserved host cell protein low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-related protein 1 (LRP1) as being a major host factor required for efficient cellular infection by RVFV.

Lrp1 is highly conserved across animals, and is found throughout the body and especially in tissues that are highly permissive to RVF infection. We recently published our study, with an outside commentary.

We have a new study out suggesting that Lrp1 may be important for other bunyaviruses too, specifically the South American orthobunyavirus Oropouche virus. Our projects are geared towards understanding how Lrp1 drives cellular infection, tropism, and cross-species transmission.

Large animal models

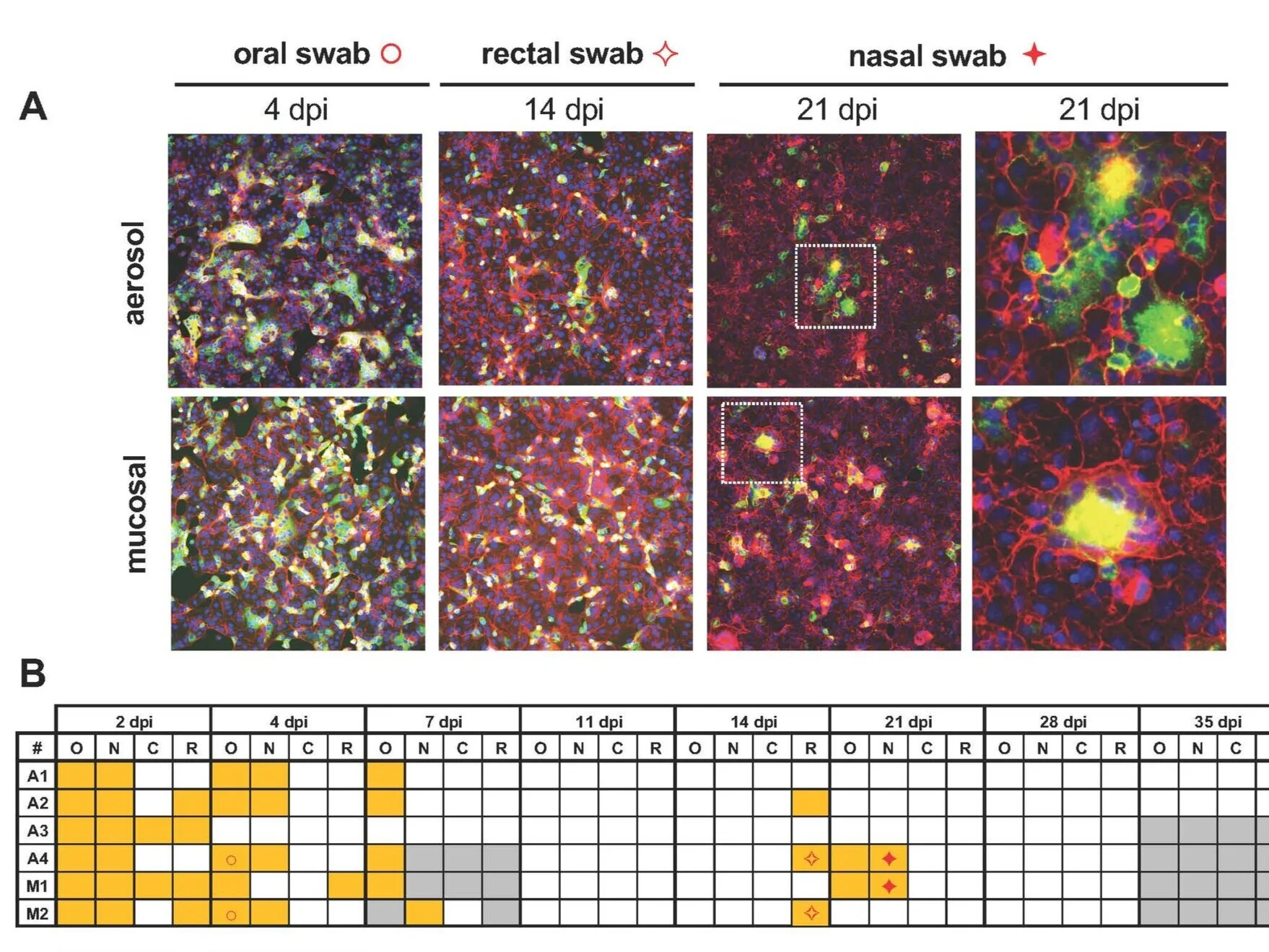

Pre-clinical evaluation of candidate vaccines and therapeutics requires rigorous, reproducible cutting-edge models that mimic aspects of human disease. This is further complicated by biosafety and biosecurity needs when working with high-containment pathogens.

Working in collaboration with our partners at the Pitt CVR, we’ve made significant advancements in understanding disease processes that are applicable to vaccine and therapeutic testing for high-hazard viruses. We provide this thorough physiological, immunological, virological, and pathological assessment. See Wonderlich et al., 2018.

Current and completed projects include animal model development, therapeutic, and vaccine testing for Rift Valley fever, the encephalitic Alphaviruses (Venezuelan, eastern, and western equine encephalitic viruses) and SARS-CoV-2.